50,000 Russian soldiers confirmed dead by BBC

Russia’s military death toll in Ukraine has now passed the 50,000 mark, the BBC can confirm.

In the second 12 months on the front line – as Moscow pushed its so-called meat grinder strategy – we found the body count was nearly 25% higher than in the first year.

BBC Russian, independent media group Mediazona and volunteers have been counting deaths since February 2022.

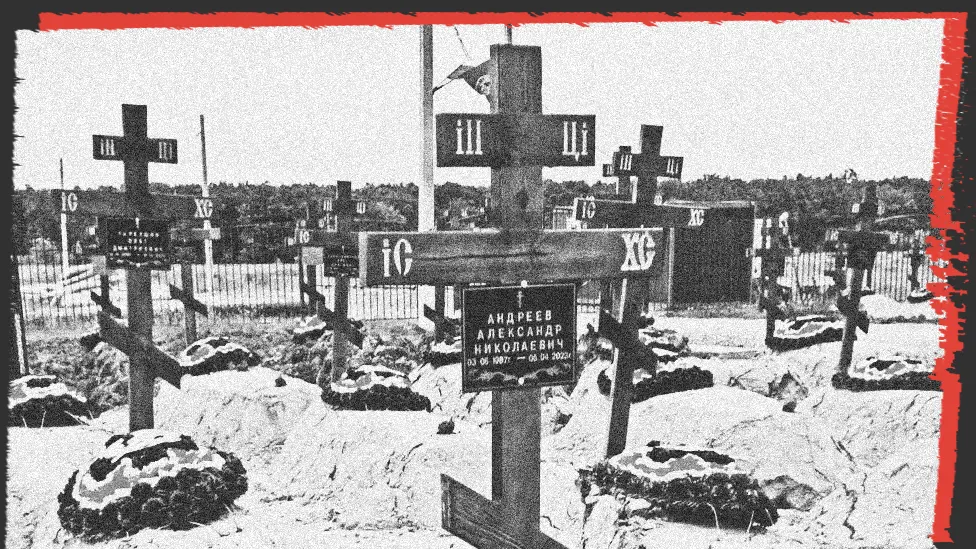

New graves in cemeteries helped provide the names of many soldiers.

Our teams also combed through open-source information from official reports, newspapers and social media.

More than 27,300 Russian soldiers died in the second year of combat – according to our findings – a reflection of how territorial gains have come at a huge human cost.

Russia has declined to comment.

The term meat grinder has been used to describe the way Moscow sends waves of soldiers forward relentlessly to try to wear down Ukrainian forces and expose their locations to Russian artillery.

The overall death toll – of more than 50,000 – is eight times higher than the only official public acknowledgement of fatality numbers ever given by Moscow in September 2022.

The actual number of Russian deaths is likely to be much higher.

Our analysis does not include the deaths of militia in Russian-occupied Donetsk and Luhansk – in eastern Ukraine. If they were added, the death toll on the Russian side would be even higher.

Ukraine, meanwhile, rarely comments on the scale of its battlefield fatalities. In February, President Volodymyr Zelensky said 31,000 Ukrainian soldiers had been killed – but estimates, based on US intelligence, suggest greater losses.

Meat grinder tactics

The BBC and Mediazona’s latest list of dead soldiers shows the stark human cost of Russia’s changing front-line tactics.

The graph below shows how the Russian military suffered a sharp spike in the number of deaths in January 2023, as it began a large-scale offensive in the Donetsk region of Ukraine.

As Russians fought for the city of Vuhledar it used “ineffective human-wave style frontal assaults”, according to the Institute for the Study of War (ISW).

“Challenging terrain, a lack of combat power, and failure to surprise Ukrainian forces”, it said, led to little gains and high combat losses.

Another significant spike in the graph can be seen in spring 2023, during the battle for Bakhmut – when the mercenary group, Wagner, helped Russia capture the city.

Wagner’s leader, Yevgeny Prigozhin, estimated his group’s losses around that time to be 22,000.

Russia’s capture of the eastern-Ukrainian city Avdiivka last autumn also led to another surge in military deaths.

Counting graves

Volunteers working with the BBC and Mediazona have been counting new military graves in 70 cemeteries across Russia since the war started.

Graveyards have been expanded significantly, aerial images show.

For example, these images of Bogorodskoye cemetery in Ryazan – to the south-east of Moscow – show a whole new section has appeared.

Pictures and videos taken on the ground suggest most of these new graves belong to soldiers and officers killed in Ukraine.

The BBC estimates at least two in five of Russia’s dead fighters are people who had nothing to do with the country’s military before the invasion.

At the start of the 2022 invasion, Russia was able to use its professional troops to conduct complicated military operations – explains Samuel Cranny-Evans of the Royal United Services Institute (Rusi).

But a lot of those experienced soldiers are now likely to be dead or wounded, says the defence analyst, and have been replaced by people with little training or military experience – such as volunteers, civilians and prisoners.

These people can’t do what professional soldiers can do, explains Mr Cranny-Evans. “This means they have to do things that are a lot simpler tactically – which generally seems to be a forward assault onto Ukrainian positions with artillery support.”

Wagner v the defence ministry

Prison recruits are crucial to the success of the meat grinder – and our analysis suggests they are now being killed quicker on the front line.

Moscow allowed leader Yevgeny Prigozhin to begin recruiting in prisons from June 2022. The inmates-turned-fighters then fought as part of a private army on behalf of the Russian government.

Wagner had a fearsome reputation for relentless fighting tactics and brutal internal discipline. Soldiers could be executed on the spot for retreating without orders.

The group continued to recruit prisoners until February 2023, when its relationship with Moscow began to sour. Since then, Russia’s defence ministry has continued the same policy.

Prigozhin staged an aborted mutiny against Russia’s armed forces in June last year – and tried to advance towards Moscow before agreeing to turn back. In August, he was killed in a plane crash.

Our latest analysis focused on the names of 9,000 Russian prison inmates who we know were killed on the front line.

For more than 1,000 of them, we confirmed their military contract start dates and when they were killed.

We found that, under Wagner, those former prisoners had survived for an average of three months.

However, as the graph above suggests, those recruited later by the defence ministry only lived for an average of two months.

The ministry has created army units commonly known as Storm platoons, made up almost entirely of convicts.

Similarly to Wagner’s prisoner units, these detachments are reportedly often treated as an expendable force thrown into battle.

“Storm fighters, they’re just meat,” one regular soldier, who had fought alongside Storm members, told Reuters last year.

Recently, Storm fighters were instrumental in the months-long battle to capture Avdiivka.

The city fell to Russia eight weeks ago and represented the biggest strategic and symbolic battlefield victory for Putin since Bakhmut.

Prisoners sent straight to front line

Under Wagner, new prison fighters were given a fortnight of military training before heading to the battlefield.

By contrast, we found some defence ministry recruits were killed on the front line in the first two weeks of their contracts.

The BBC has spoken to families of prison recruits who died – and soldiers still alive – who told us the military training offered to prison recruits by the defence ministry is insufficient.

One widow told us her husband had signed his ministry contract in prison on 8 April last year – and he was fighting on the front line three days later.

“I had been sure that there would be the few weeks of training they talk about. And that there’d be nothing to fear until at least the end of April.”

She said she waited to hear from him – but found out that he had been killed on 21 April.

Military graves at Bakinskaya cemetery in southern Russia

Another mother says she only found out her husband had been taken from prison to the battlefield when she tried to contact him about the death of their son, who had also been fighting.

The woman, who we are calling Alfiya, says her 25-year-old son Vadim – a father of twins – had never held a weapon before being mobilised.

She says she couldn’t tell her husband Alexander about their son’s death because he had been “taken away” to fight. She only found out he had gone via a phone call from another inmate.

Alexander grew up in Ukraine and had family there – says Alfiya – and he knew it was “a lie” that Russia had invaded Ukraine to fight fascism. When army recruiters first came to the prison “he sent them to hell,” she says.

Some seven months after the death of her son, Alfiya was informed that Alexander had also been killed.

‘Be ready to die’

When working for Wagner, prison inmates were typically contracted for six months. The fighters – if they survived – would then be given their freedom at the end.

But, since last September, under the defence ministry, enlisted prisoners must fight until they die or the war is over – whichever comes first.

The BBC has heard recent stories of prisoners asking relatives to help them buy proper uniforms and boots. There have also been reports of inmates being sent to fight without proper kit, medical supplies or even Kalashnikov guns.

“Many soldiers had rifles that were unsuitable for combat,” writes Russian war supporter and blogger Vladimir Grubnik, on his Telegram channel.

“What a foot soldier should do on the front line without a first aid kit, a spade to dig in a trench and with a broken rifle is a big mystery!”

ReutersYevgeny Prigozhin, late chief of Russian private mercenary group Wagner

ReutersYevgeny Prigozhin, late chief of Russian private mercenary group Wagner

Grubnik – who is based in Russian-occupied eastern Ukraine – claims when commanders found out that some guns were “completely broken” they said it was “impossible” for them to be replaced.

“The rifle was already assigned to the person, and the harsh military bureaucracy couldn’t do anything about it.”

Former prisoners have also described the high price paid by their comrades.

“If you sign up now, be ready to die, mate,” says Sergei, in an online forum for Storm fighters and their relatives, where information is shared.

He claims to be a former inmate who has been fighting in a Storm unit since October.

Another forum member says he joined a Storm platoon of 100 soldiers five months ago and is now one of just 38 still alive.

“Every combat mission is like being born again.”

BBC